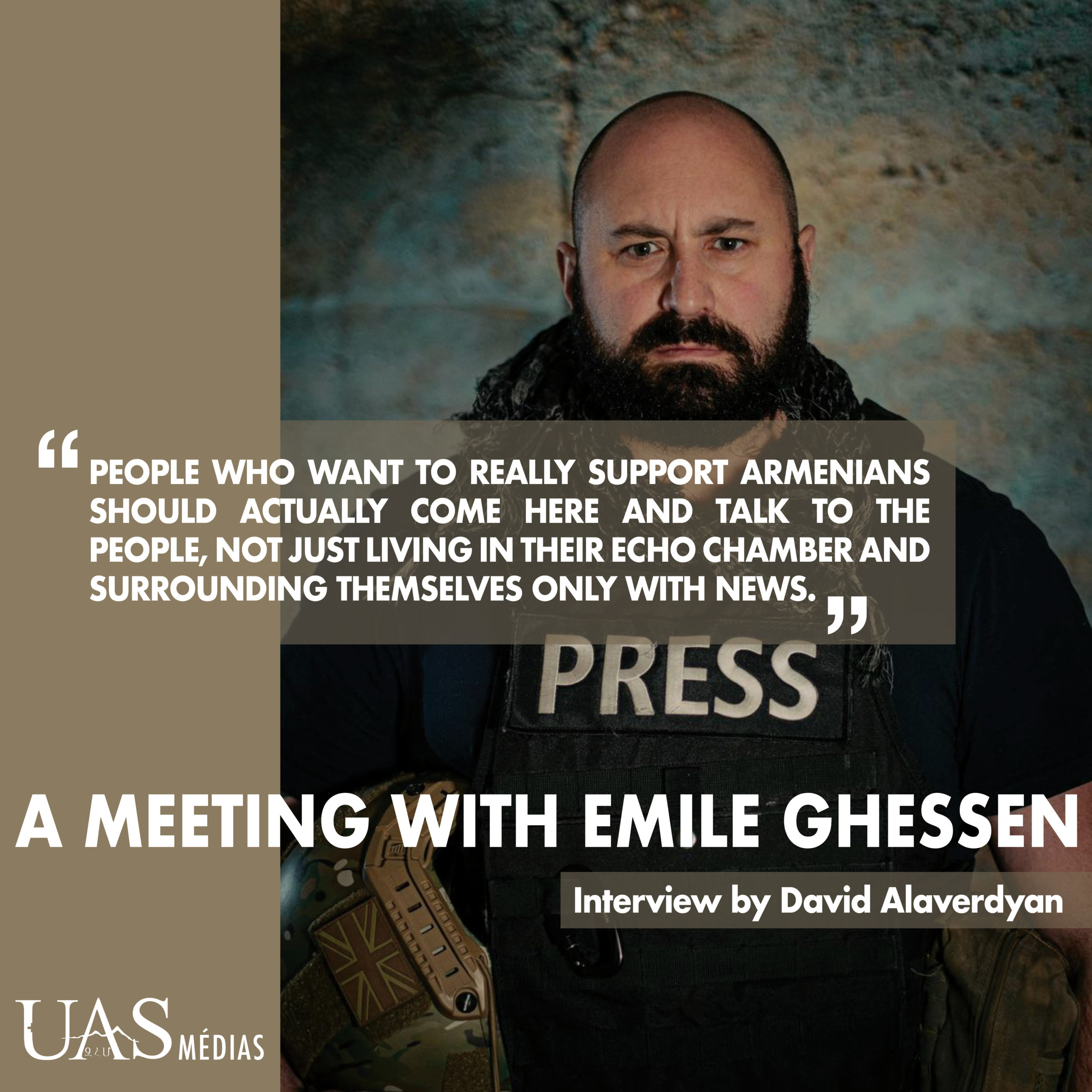

David Alaverdyan, a young armenian from the community of Switzerland, had the opportunity to meet Emile Ghessen, a former Royal Marines Commando and documentary filmmaker from Britain ; here are David’s thoughts :

« During the 2020 war in Artsakh, I noticed on social media people talking about this British reporter who was reporting on the frontline. Later, during the summer holidays, I was in Yerevan, at the same time he was, and I heard he was preparing a documentary on the war. I wanted to meet him and interview him, to know more about his project, and also himself. It has been a real pleasure. » (David Alaverdyan, 19 years old, student in international relations)

Can you first tell me about your experience as a Royal Marines : why did you engage, what was your rank, and where were you deployed, and why did you decide to become a war journalist?

I served as a Royal Marines commando in Britain for 12 years, I joined in 2000 and went to Afghanistan just after 9/11. Then I was deployed in the invasion of Iraq, then back to Afghanistan in Helmand province. We were quite busy during that period in the military, with the war and terrorism going on. Then I left the military in 2012 and went into private security work. I was doing anti-piracy work against Somali pirates attacking commercial vessels, and some bodyguarding work. Then what happened was the war in Syria (my father is Syrian), and I met a guy in a bar that was going to fight ISIS. I was intrigued by what was motivating him to go fight, so I decided to buy a camera with no experience and make a first feature documentary. I was out in Iraq, Syria, filming what motivated men to go fight against the Islamic State. From there I went to film school and after that, I went to Ukraine to make another documentary on men who are fighting the pro-Russian separatists, from the Ukrainian perspective. Then the war started here, and the world was in lockdown because of the pandemic, and I found it very interesting, the fact that it was a conventional war between two sides, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Most of the conflicts I have fought and been involved in and filmed have been between non-conventional forces, other than the invasion of Iraq, so for me it was very intriguing. And knowing that there was a lot of information about drone warfare and the advancement of technology in the war, so I decided to come to Armenia to cover what was going on. The reason I came to Armenia rather than Azerbaijan is because I was filming the Kurds in Syria and Iraq, so I know about the Turkish influence they had there, and Turkey joining Azerbaijan, I thought it was more of an interesting story to tell from the perspective of a small Christian nation that is being under constant threat.

You also have been in migrant camps ; you have been a bit travelling the road with some migrants.

I have travelled with migrants as well, following them, mainly because it was personal to me, many of them were Syrian, so I understood the truth. Everything I do is humanization work. I have fought in war for years, I understand war and to me, war, of course it is exciting, but the human story is more exciting and telling that story is what I try to do with my films : tell the human story, (the story of) the people who suffer from war. That is what we have done with the 45 Days documentary here, in Armenia, to tell the human side. It is not a political agenda, it’s totally independent, it is telling the human perspective from the Armenians.

You have been in Karabakh since almost the beginning of the conflict : what do you remember the most, what is the most marking memory?

The hardest part that I have seen is after the trilateral peace agreement was signed on the 10th of November when the civilians were told, from certain regions of Karabakh, that they lost their territory and they were handed over to Azerbaijan, it is being with the families when they are packing up their homes, putting their belongings into cars, burning their homes down. To me, that was more impactful than the actual war, because it was the cost of the war, seeing firsthand that the people are the ones suffering. That is what we have done on this journey of 45 days, we try to cover these stories: the stories who are untold and give a voice to the voiceless. The soldiers are of course an important part of the story. However, when I was a soldier and I was going off to war, I didn’t really think about how I had an impact on my family, and as a journalist and filmmaker, I see the impact it has on people. Especially in Armenia, the fact is that everyone knows someone who went to fight or someone who died, it is not just like the British or American forces who went to fight in Afghanistan in a far-away land. It is all of Armenia and the diaspora that have all been affected by what was going on there.

It is only a country of 3 million people, so of course a lot of people have relatives from Karabakh or indeed people who went to the front line.

There is also a lot of intergenerational trauma that I felt in Armenia. Most of the diaspora has moved not by choice, but by hardship, from the genocide, from the massacres and then from the fall(collapse) of the Soviet Union. People have been displaced, and I pick up on the fact that the diaspora is so connected to Armenia, and they felt especially during this war that they and their homeland were under threat.

For you, this conflict was different from the others before because the previous ones you had armed groups fighting one another, and here you had two nations fighting. You said it is the first one?

It is. Drones were the biggest contributors for Azerbaijan winning this war. When I was in the military, we used drones, but we never used them to scale the Azeris used, supported by Turkey and Israeli arms deals. And the fact is that young Armenian soldiers with very little training were fighting with weapons as old as their fathers and grandfathers against modern-day technology. It was very much David vs. Goliath in the sense that one side was superior. I also think that the timing for the war was perfect in the sense that the world was in lockdown, every country had its problems with covid, and the US elections were very instrumental. Azerbaijan and Turkey chose the right time. September until October is close to the end of fighting season: any military commander would know this is coming to an end, and if you need a push you need to do it before winter, especially in the Karabakh region where the snow comes in very quickly. Even if the timing were perfect, from my experience of what I saw, I don’t think the Azeris thought the war would go on for 44 days, they probably thought it would be a lot shorter. It was still a very quick and decisive win, however, the Armenians were very determined, and they held on for as long as they possibly could. And this is what we talk about in the documentary, about what happened, and the personal stories of the soldiers. The reason we named the film 45 days even if the war was 44 days, is because the 10th of November was the 45th day. I was in Republic Square when the announcement was made. Then I moved to Goris where I met the Russians as they moved in on the 45th day. So, the turning point of the future of Armenia lasted up to the 45th day.

How was the atmosphere on the Republic square or in Yerevan when the announcement of the defeat was made?

Here in Armenia, it was around 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning. I was in my hotel room planning to go back to Karabakh the next day to continue filming the war. Then I got a phone call saying, “I think something is going on at the Republic square”. So, I came down to Republic square and there were thousands of people. They broke into the government building, there wasn’t any defense because it was very unclear what was going on, no one really knew. In the early morning, we were speaking to people, and they were saying “we have won the war” while others were saying “no, we have lost the war”, and no one knew. We stood in Republic square, people were on Facebook and they were listening to the prime minister announcing the defeat of Armenia and at the same time, he was not explaining clearly that the war was lost. He was at some point talking about how Armenians must fight to the end, then talking about how the government had to sign the capitulation, so people did not really know what was going on.

Indeed, one week before that, he said there will be no diplomatic solution, then there was a diplomatic solution.

And that is why people were angry and frustrated, because they did not know what was going on, and I felt that. That is why me and my cameraman decided to drive straight back to Goris. And just before the border into the Karabakh region, all the Russian tanks were there lined up, and we followed them into Karabakh back to the frontline to see what was going on. Even the Russians did not know what was going on, they were mobilized very quickly to get there. We stopped at night on the 10th of November, about 20 km short of Shushi, and me and my cameraman thought to drive to get to Stepanakert to meet the soldiers coming out. The Russians said that we could not go any further, they were the first tank moving in, and they did not know where the Azeris were and there was a breakdown of communications with the Armenians and the Azeris, it was quite confusing.

You said, even as a soldier who has been in Afghanistan and in Iraq, which were quite big operations, you had never seen this much the use of technology by a big country, right?

Yes, wars are not only fought on the battlefield with guns, but they are also fought in several different ways, there are many different layers of warfare, one of them being information war, and the use of propaganda, misinformation, disinformation, social networks, which I have seen in all conflicts, especially in Syria, Ukraine, and here in Armenia and Azerbaijan. So there is the information space, and the electronic warfare, the intercepting of phone signals, radios, computers and all, and on the battlefield it was the drone warfare. A lot of Armenian soldiers, when you talk to them about Azeri and Turkish soldiers, a lot of them would say they never saw them, they never actually saw anyone, because it was just drones, and they were sending drones. They were using surveillance to monitor where the troops were on the ground to move their forces, and they were also using drones to identify target and call-in artillery and mortars at further distance, correcting their movement to the ground. The Armenian soldiers on the ground knew when there were drones around, they were either going to get targeted by a kamikaze drone or a rocket or artillery and mortars, or smirch rockets. For a lot of guys, the sound of drones was psychologically a massive impact.

You described this conflict as a David vs. Goliath, and in this case, David lost. From your experience, as a former soldier and commander, who do you think should be held accountable?

It is a hard question, to say who should be held accountable. War is war, countries declare war and you go to war when diplomacy fails. It is too easy to just point fingers at who is to blame. I remain objective, the documentary, even though it is told from an Armenian perspective, is still objective. I am not able to lay blame. As I said, the timing was perfect for the Azeris, the window of opportunity was there, so they took advantage of that. The fact is that Artsakh conflict has not been resolved since the 90s, and the issue was sitting there all that time. For me, someone who has been in a conflict and understands conflict, it is very surprising that the Armenians were not more prepared for the war. A lot of people predicted that one day they would go to war over that region again. So, who is to blame, I do not know. Can we blame the Armenian government for what happened? To a certain degree, maybe yes, but overall, it has been for a long time that the army has been neglected in the way it was trained or equipped. And when September the 27th happened, thousands of men were mobilized in a noticeably short time with little equipment.

I understand it would be hard to blame the government, because it still brought the remaining soldiers back from the frontline. But there are still prisoners of war in Baku who are being sentenced.

The reason for the prisoners of war is I think the peace deal was rushed; they should have better put into place what they wanted to achieve at the end of it. The fact is that the majority of POWs that are being held now are the ones who were caught after the war ended. The Azerbaijanis are using them as psychological tools and a bargaining tool for mining maps. They are controlling the narrative on these men. They say they were captured after the 10th of November. They are not calling them prisoners of war, but terrorists. If they are POWs, the international community can be involved. But what they are doing very cleverly is saying they are not soldiers, but terrorists. They are then trialed (sued) for domestic charges. It is very manipulative of what the actual word is. They are taking soldiers who belong to the Armenian military or the Artsakh defense force and branding them as terrorists, which is totally unacceptable. To be honest a lot of the international community should put more pressure on Azerbaijan to release these men, because they are being used.

But is the international community putting pressure?

I don’t know exactly who. I know there were some politicians in the UK who were very vocal about it, saying we need to speak up. But the geopolitics trumps over human rights and there is the issue we are seeing here. Countries do not want to annoy Azerbaijan or Turkey for geopolitical reasons.

Because they give them oil and stadiums for sporting events.

Yes, so it is a tough one, but there are still thousands of families and family members who are still waiting for their loved ones to come home. And it is unacceptable the fact that they are being branded terrorists, when they are not, they are soldiers. It’s like me fighting in Iraq or Afghanistan and being captured and then people would say I am a terrorist. But no, I am here because my government sent me here. It’s a manipulation of the word itself and on who is what.

Concerning the Azerbaijani manipulation, for someone who has fought and seen many wars, have you seen many leaders like Aliyev, who is a leader driven by violence and desire for war, almost like a modern-day Hitler?

Well, the fact is that during a time of war, leaders need to be seen strong to their people. I think at the time before the war, Aliyev was not very popular, and a good way to get popularity is to take your country to war, unite them against a common enemy. In that way, the people forget about domestic issues and focus on international issues. The rhetoric during the war and after the war from Erdogan and Aliyev was very aggressive. In many interviews they call Armenian rats, dogs and subhumans. And that trickles down in the Azeri and Turkish society. We are all normal people, we all want the same things in life, but when a government is directing the narrative, it does have an influence on its people, and I have seen that quite a lot here.

About the hate in the Azeri society, they also teach at school to young children that Armenians are just dogs and rats. After the Azeri victory, the regime built the victory park. What is your view on that?

They call it a victory park, and I can see why many Armenians were hurt by that. I think it’s a cheap low from Azeris, it was very distasteful. You could see the wax models, that whoever was commissioned to make them, did not do a very good job, because they were trying to visualize Armenians as ugly people, with big noses. It was very much a manipulative kind of gesture. Children are being taken there and are being used as propaganda. I could understand the fact that they had a victory parade, because if Armenia had won, they would have done the same. So, it is distasteful, things like museums or parks. Of course, a museum why not, but here they have done it very quickly and very distastefully.

In my opinion, it is a bit like during the war in Vietnam, the US would picture the Vietnamese and communists as big monsters and hideous people…

Yeah, that is all part of the propaganda, it is part of building up your nation to want to go to fight because they feel that the ones they are fighting are evil and bad. Even our government has done it with people like Saddam Hussein or Oussama bin Laden. They try to rally the people in a hate campaign. You mentioned Hitler, he did the same against the Jews. If you have a problem, it’s not because of the government but because of these people, this selects few. And I think Azerbaijan has done the same with Armenians, trying to get their people to rally behind them, to hate someone for no reason.

What were the strong and weak points of the Armenian military, besides the old equipment and the young population?

I think the issue with the Armenian military is that they are trained and prepared in an old way. I look at them as an objective person and see that they still have the soviet mentality, especially in the high command, and how they fight wars. Turkey is a member of NATO, Azerbaijan is not in NATO, but their military is more NATO standard. They have invested in their military, they have trained their men into a certain way of fighting, NATO style. Armenia has not, because they have been very reluctant to spend money, because the investment in Armenia is low, the GDP is low, there is less money to be put in the military. But I think they could easily reform this, they could start training the commanders on how to move forward. The soviet mentality needs to change, and it could be easily achieved.

It’s still a very soviet life here, you have soviet cars, some buildings from soviet times from the 60s or 70s, so the soviet mentality is quite implemented here.

Yeah, and it is because Armenia’s population is a very small population. It’s smaller than most European and American cities, and the money the government must spend is also limited.

We talked a bit about the diaspora, what’s your opinion on the Armenian diaspora? It’s more than 3 times bigger than the population of Armenia. During the war, people have been doing protests, being active on social media, donating to charities in link to the war, some even went to the frontline. Should the diaspora have done something more?

I think the diaspora was very vocal, like we saw in L.A. where highways were shut down, which is massive, and through other protests throughout Europe, also in Australia and Argentina. But I think they were limited; their hands were tight. I spoke to a lot of diaspora people, many new friends. They have a sense of guilt amongst a lot of them, they felt helpless because they could not do more. But financially, the diaspora was brilliant, like sending money for help, and money goes so far. Even for our project, most people who donated were from the diaspora. So, when it comes to money, the diaspora across the world has been great. I think the difference between the diaspora and the people of Armenia is they want two different things for Armenia. And now that the war has ended, the diaspora needs to do more. During the war they were of great support, and when the war was over, they took their foot off the gas, they thought: “ok, we tried to help, we failed, what can we do now?”. And now is the time the diaspora needs to come back to Armenia, invest in Armenia, there is a lot of potential here, with quite some workforce, they need to pump money in the economy. Many Armenians from the diaspora feel under threat. Many of them were not even born in Armenia, they are like second or third, sometimes fourth or fifth generation. We couldn’t compare Armenia to Israel, there are some similarities, but very few. Armenians feel under threat mainly because of the genocide, because of the Soviet Union, how so many were pushed out of the country. So, they feel that by the defeat of the war, they lost parts of Artsakh and they are still losing territories, and that eventually Armenia will disappear. And I think that is why there is so much frustration in the diaspora, they feel they are going to lose the country. I think this is the time when they need to come back, invest and make their country stronger, bringing in foreign investment in the country. For example, I had a conversation with someone here about McDonalds, wondering why there aren’t any McDonalds in Armenia? People here say they don’t want fast food, but it’s not about fast food, it’s about what comes with these large corporations, which is investment and foreign influence. So, when diplomacy fails, you have large companies like Google, Microsoft, Coca-Cola, all of those, when they have financial interest in the country, they do not want war, they want to keep stability in a nation. Armenia’s future is limited with the Russian influence, so they need to start an investigation in American and European investment here.

But it has been since quite some time that it is said that the diaspora must return to invest and help the country grow, but no one is really doing it, because the salaries are low, no real valuable resources to be exported, unlike the Azeris with oil for example. So, big corporations might be the solution, but after economic growth, the country could be in their pocket, in their debt, and perhaps, Armenians could lose their identity?

I think this is the issue with Armenians, they have been persecuted for years, struggling with this identity thing, always wanting to preserve their identity. Even when it comes to Christianity: a lot of people I know aren’t really Christians. Well, they are, but not really. The only reason they hold on to Christianity because it’s an identity for Armenia as the first Christian nation. Of course, every country has influence, every successful country has some sort of influence, and that’s the way Armenians should look at it that way. And a lot of the diaspora talk about coming back here but they just keep on coming here for their summer holidays, staying two or three weeks. But when you speak to the Armenians from the diaspora, who love Armenia, you ask them: «you’re going to come live here?” they say “oh I would love to but-” and there is always a “but”. And it is as you said there isn’t really any money here as in terms of low wages, and people like their comfortable life in Europe and America, they don’t want to sacrifice that. They want their children to go to a good school, they see the schools here and think the schools are good but are not as good as what their children could have. So, I understand why people of the diaspora are reluctant to move here. However, at the same time, the big corporations should invest here, because the GDP is low, the workforce is cheap, but there are still a lot of intellectual Armenians, there is a lot of potential in this country. They could invest into the country, employ people, slightly increase the wages so that it generates more money for the economy here. But the issue is that a lot of people distrust the government, I spoke to someone yesterday, that has a software business and wants to invest in the country, but he is struggling to do that, to commit to it because he distrusts the government, and that’s the issue here: the government should be more welcoming to the diaspora, they need to allow them to operate a little bit easier here, to bring that investment to the country, to assist everyone!

Some Armenians who have been active on social media during the war and after, have been strongly criticizing the diaspora members who only come to Armenia in the summer and spend their money in restaurants and in fancy places, rather than spending some of their time helping the people in need and donating to charities. What do you think about that?

I think among the people there is a lot of distrust, a lot of people from the diaspora felt as if they donated money but the war was still lost, to organizations like Armenian fund. And smaller NGOs have popped up on social media that sent the donated money directly to soldiers and their families, so a lot of people have done great work. But there’s also a lot of hate as you said, a lot of people hate those who just go to cafes and bars. But at the same time, those who are going to cafes are investing. They’re consuming and spending money, so money is going into the system and into the economy, so I don’t think people in Armenia should be hating on the ones from the diaspora who come and spend time here, at least they are coming to the country. I think there is much shaming and naming and finger pointing, which I think is unacceptable. I don’t think that someone saying: “you should have donated 5 dollars to save that person’s life” doesn’t try to shame people into doing anything, all I am saying is come to Armenia and spend some time here. And the Armenians that live here, they welcome the diaspora, they are happy to see the diaspora. It’s helping the economy; it is helping their families. So, if no one came here, the people would be struggling. And I think the resilience of the Armenians has been brilliant, I’ve seen it in the war, after the war, after Christmas, during the elections, and I have seen it very differently during the whole time in the sense that the mood has changed in the country. I’m being objective and totally independent, but it’s good to have many Armenians from the diaspora coming here and wanting to spend their time here, because many of them felt they couldn’t because of the war. Most of them were restricted from coming here, or their families wouldn’t let them, or they had to work and so on. But the plus side of Covid -one of the rare ones- is that people work remotely. During the war, you had people in the diaspora working here, helping the soldiers and families, and doing their normal job working remotely, so people say: “no, you’re there just sitting in bars”. Most people are doing their jobs but working remotely, so in the evening, why couldn’t they go to a bar or dance. During WWI, men were in the trenches, while two miles behind, people were in bars, drinking, dancing, and singing. That’s a sign that the resilience of life goes on. I’ve had a lot of hate on social media asking why I am out, why I seem happy, why am I smiling. It’s resilience, life goes on. You cannot just sit there and mourn, the country needs rebuilding, it is the time.

I remember when I came here, it felt weird because it felt as if nothing happened, I didn’t feel any mourning atmosphere or anything close to it, but what you say is right, sometimes life has to go on.

Many of the people of the diaspora, and that’s not me hating on the diaspora, come talking to me, on social media or others asking why Armenia is like that, why they are doing this, seeming to be happy. But when they come here, they change their tune, feeling more at peace and more understanding of the vibe. People from the diaspora are far away, and with the distance can come sometimes disinformation like on social media. Just because people sit in bars and are smiling, it doesn’t mean that they forgot about what happened here, they don’t forget about the families that are suffering, soldiers that are suffering from PTSD or depression. People have to get on with their lives, and that’s what people do here, and when Armenians of the diaspora come and see that, they pick up on this vibe, which is good. It’s easy to be miles away and judge, until you are there.

People who want to really support Armenians should actually come here and talk to the people, not just living in their echo chamber and surrounding themselves only with news. Coming and talking to people is what we have done in the 95 minutes documentary film: to show that these are the people who lived the story, people on who the war had a real impact. A lot of people of the diaspora have also been affected, but it’s really the people who live here day in day out, they are the ones that are really affected by it. They are the ones affected by the politics, they are affected by the conditions and the things that are going on here. So people who have houses miles away, of course they can have an opinion, but come to Armenia and actually see what is going on here.

With the UAS, we thought about inviting you someday to Geneva, so that you can present your film and meet the Armenian community of Switzerland and Geneva. Do you think you could do that sometime in the future?

Well, now, we are releasing the documentary next week on the 20th of August in the Moscow cinema in Yerevan, then we’re going to America, to release it in cinemas, and then it will be Europe, so when we will be planning the dates for Europe, we can agree to it. But for the moment, the issue is covid restrictions and visas, which is the biggest limitation we had for this documentary. Even if we have done it in 10 months, we still had some delays due to Covid.